Friday, August 28, 2009

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Friday, August 21, 2009

Thursday, August 20, 2009

Monday, August 10, 2009

Tasers

Representatives of the government torture innocent citizens into unconsciousness, on camera, in United States courtrooms with tasers. They use them on prisoners and on motorists and on political protesters and bicycle riders, on mentally ill and handicapped people and on children And it's happening with nary a peep of protest.

America's torture problem is much bigger than Gitmo or the CIA or the waterboarding of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. The government is torturing people every day and killing some of them. Then videos of the torture wind up on Youtube where sadists laugh and jeer at the victims. It's the sign of profound cultural illness.

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Lodge Doctors

Fraternal organizations, like the Sons of Telsh, hired physicians to treat members and their families in return for a set annual fee. Numerous immigrant groups in urban areas engaged doctors in this way, but commentators associated the system especially with New York Jewish burial societies.

The system of hiring doctors gave society members access to primary health care. But just as importantly, it preserved the immigrants' sense of dignity and guaranteed them a great deal of power in the doctor-patient relationship. For the cost of $2-3 (the cost of one or two visits from a private physician), an immigrant family could enjoy the services of a society doctor for the entire year. The services of the lodge doctor resembled those of a private physician in that treatment was carried out at the home, and therefore at the convenience of the patient. Inexpensive access to medical care probably encouraged early treatment, may have prevented the progression of disease, and definitely limited the use of patent medicines and folk healers.

The system also benefited the doctors. A recently graduated physician could build up a practice by securing a society contract, while he built up an independent clientele. Physicians who were immigrants themselves often had a limited pool of potential patients, since they faced social and cultural barriers to practicing outside their immigrant community. The medical profession was particularly popular among Eastern European Jews in New York; a 1906 study reported on the overabundant supply of physicians.

Serving as a society doctor was hard work. Physicians sometimes served as many as ten different fraternal organizations. An article in the Tageblat estimated that the lodge doctor might see upwards of 100 patients a day. Not, surprisingly, the hours were long. For example, Dr. Freedman had office hours from 8-10am, 2-3pm, and 6-8pm. In addition, he had to make house calls, frequently over a wide geographic area. Forced to climb up and down tenement stairs, lodge doctors found their patients exceedingly demanding. Physicians' harried schedules and inexperience sometimes compromised the quality of care provided by lodge doctors. The Tageblat reported, "sad is the life of the lodge and society doctor, but sadder still is the suffering of the majority of patients who are treated by this sort of doctor."

Members of burial societies did not have to resort to public dispensaries, like the Good Samaritan Dispensary at the corner of Broome and Essex Streets, or hospital clinics, the other major healthcare providers for the poor, which carried the stigma of charity. Dispensaries, the main alternative to contract medicine, had all its deficiencies plus the taint of charity. Like their colleagues in society practice, dispensary doctors faced overwhelming workloads. Patients waited for hours in crowded conditions for perfunctory examinations. The doctors, frequently hailing from a different ethnic and class background than their patients, were viewed with suspicion. After 1899, because of a law, only the indigent could visit dispensaries. Thus, use of the clinics constituted a public declaration of penury and left the patients open to a range of intrusive investigations regarding their worthiness for medical care.

Pro:

The services of the lodge doctor resembled those of a private physician in that treatment was carried out at the home, and therefore at the convenience of the patient. Inexpensive access to medical care probably encouraged early treatment, may have prevented the progression of disease, and definitely limited the use of patent medicines and folk healers.

The system also benefited the doctors. A recently graduated physician could build up a practice by securing a society contract, while he built up an independent clientele. Physicians who were immigrants themselves often had a limited pool of potential patients, since they faced social and cultural barriers to practicing outside their immigrant community.

Con:

Physicians sometimes served as many as ten different fraternal organizations. . . .the lodge doctor might see upwards of 100 patients a day. Not, surprisingly, the hours were long. For example, Dr. Freedman had office hours from 8-10am, 2-3pm, and 6-8pm. In addition, he had to make house calls, frequently over a wide geographic area. Forced to climb up and down tenement stairs, lodge doctors found their patients exceedingly demanding. Physicians' harried schedules and inexperience sometimes compromised the quality of care provided by lodge doctors.

Compared to What?

Members of burial societies did not have to resort to public dispensaries, like the Good Samaritan Dispensary at the corner of Broome and Essex Streets, or hospital clinics, the other major healthcare providers for the poor, which carried the stigma of charity. Dispensaries, the main alternative to contract medicine, had all its deficiencies plus the taint of charity. Like their colleagues in society practice, dispensary doctors faced overwhelming workloads. Patients waited for hours in crowded conditions for perfunctory examinations. The doctors, frequently hailing from a different ethnic and class background than their patients, were viewed with suspicion. After 1899, because of a law, only the indigent could visit dispensaries. Thus, use of the clinics constituted a public declaration of penury and left the patients open to a range of intrusive investigations regarding their worthiness for medical care.

Medical Care Before the Welfare State, 1900-1930

On the face of it, a historical study of fraternal societies seems to be a subject fit only for connoisseurs of the arcane. Few Americans these days come into contact with such groups. When many of us hear the word lodge, we think of it as a place where television characters from our youth, such as Ralph Kramden (of the Loyal Order of Raccoons) and Fred Flintstone (of the Loyal Order of Water Buffalos), escaped from their more sensible wives to engage in childish hijinks—parading around with silly hats and mouthing pretentious rituals.And what happened to these what must be judged on the whole as successful private social service initiatives?

There was a time, however, when fraternal societies could not be so easily dismissed. Before the rise of the welfare state, they were rivaled only by churches as organizational providers of social welfare. By conservative estimates eighteen million American men and women were members in 1920 at least three out of every ten adult males. While fraternal societies differed in ethnicity, class, and gender, most shared a common set of characteristics. In general, this included a decentralized lodge system, some sort of ritual, and the payment of cash benefits in times of sickness and death.

By the turn of the century, an increasing number of societies began to add treatment by a doctor to their menu of services. This arrangement was known as lodge practice. It involved a simple contract under which a physician provided care in exchange for an annual salary determined by the size of lodge membership. To qualify, a prospective lodge doctor had to win an election by the members. Generally lodge practice plans did not extend beyond basic primary care and minor surgery, although a few provided hospitalization.

Lodge practice became particularly extensive in urban and industrial centers. In 1915, for example, Dr. S.S. Goldwater, Health Commissioner of New York City, went so far as to assert that in many communities it had become “the chosen or established method of dealing with sickness among the relatively poor.” In the Lower East Side of New York City, he noted, 500 physicians catered to Jewish societies alone. Among blacks in New Orleans there were over 600 fraternal societies with lodge practice during the 1920s.

The most important beneficiary of lodge practice was, of course, the patient of modest means. He or she was able to obtain the care of a doctor for about two dollars a year roughly equivalent to a day’s wage for a laborer. If translated into 1994 dollars, this annual fee would be equivalent to about 14 dollars, the hourly wage of some construction workers today!

The remuneration paid to the lodge doctor was a far cry from the higher fee schedules favored by the profession. A local medical society in Pennsylvania was typical in setting for its members the following minimum fees: one dollar per physical examination, surgical dressing, and housecall (daytime) and two dollars (nighttime). Such prices, at least for continual service, would have been out of reach for many poor Americans.

Even before the Depression, lodge practice had begun to fall into a state of decline. The pressure exerted by the leaders of organized medicine hastened the demise. By the 1910s, doctors had launched an all-out war against lodge practice. Throughout the country, medical associations imposed a range of sanctions against lodge doctors, including expulsion from the association and denial of hospital facilities. In certain instances, campaigns were organized to deny patient care, even in emergencies, to members of offending lodges. Most commentary from both sides of this conflict indicates that these sanctions were highly effective. In any case, by the end of the 1930s, the once vibrant health care alternative of lodge practice, which less than two decades before had inspired trepidation throughout the medical establishment, had virtually disappeared.

Over time the AMA was successful in establishing a cartel

A standard response to the suggestion that society can be ordered and organized by non-coercive means is what Stefan Moylneux calls the Argument from Apocolypse.1913

AMA establishes a "Propaganda Department" to gather and disseminate information concerning health fraud and quackery1922

Judicial Council amended The Principles of Medical Ethics, outlawing the solicitation of patients by physicians, a policy that remained in effect until the new Principleswere adapted in 19801934

During the Depression, the Judicial Council amended the Principles by making it unethical for any physician to dispose of his or her services to any lay body, organization, group, or individual under the conditions that would permit any of them to receive a profit on the doctor's services

The basic argument is that if we accept proposition “X,” civilized society will collapse, children will die in the streets, the old will end up eating each other, and the world will dissolve into an endless and apocalyptic war of all against all.

When it is suggested that perhaps the federal government might not be capable of engineering the health care "system" it means, of course, you want to keep things as they are now, only worse because you want old people to eat dog-food and die in the streets of swine flu!

But there was a time when ease of entry, voluntary association and price competition--in other words, a free market--provided normative health care to the "poor" without the enforcement arm of the state.

I Did Not Know This

The Federal Reserve can enter into agreements with foreign central banks and foreign governments, and the GAO is prohibited from auditing or even seeing these agreements. Why should a government-established agency, whose police force has federal law enforcement powers, and whose notes have legal tender status in this country, be allowed to enter into agreements with foreign powers and foreign banking institutions with no oversight? Particularly when hundreds of billions of dollars of currency swaps have been announced and implemented, the Fed’s negotiations with the European Central Bank, the Bank of International Settlements, and other institutions should face increased scrutiny, most especially because of their significant effect on foreign policy. If the State Department were able to do this, it would be characterized as a rogue agency and brought to heel, and if a private individual did this he might face prosecution under the Logan Act, yet the Fed avoids both fates. More...

Now I do.

H.R.1207: Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2009

S.604: Federal Reserve Sunshine Act of 2009

Nock: Turning Every Contingency Into A Resource

. . .many of our people were in hard straits; to some extent, no doubt, through no fault of their own, though it is now clear that in the popular view of their case, as well as in the political view, the line between the deserving poor and the undeserving poor was not distinctly drawn.

Popular feeling ran high at the time, and the prevailing wretchedness was regarded with undiscriminating emotion, as evidence of some general wrong done upon its victims by society at large, rather than as the natural penalty of greed, folly or actual misdoings; which in large part it was.

The State, always instinctively "turning every contingency into a resource" for accelerating the conversion of social power into State power, was quick to take advantage of this state of mind. All that was needed to organize these unfortunates into an invaluable political property was to declare the doctrine that the State owes all its citizens a living; and this was accordingly done.

It immediately precipitated an enormous mass of subsidized voting-power, an enormous resource for strengthening the State at the expense of society

Friday, August 7, 2009

Hypothetically Axiomatic Praxeology

In every voluntary exchange both exchange partners must benefit from the exchange, otherwise the exchange would not have taken place.

Is this statement hypothetical or axiomatic?

Is it akin to saying the world consumes twice as much beef than pork or an object cannot be in two places at the same time?

The former could be reversed without saying something patently absurd: The world consumes twice as much pork than it does beef. It can also be tested. The latter, though, an object can be in two places (or more) at the same time is nonsense on the face of it (except perhaps on some quantum level that has nothing to do with faces smacking into windshields). How could you even construct a test to prove, or better, falsify it? According to Karl Popper, if you can't test it it's not true. But you can't test it except to examine every particle in the universe. Is it any less true regardless?

So is the statement about voluntary exchange of the type the world consumes more beef than pork or an object cannot be in two places at once?

The thing is, obscure as that might be, as much as you may see angels dancing on the head of a pin, so much about the study of economics as a science flows from the answer to that question that I shudder to think that the people who have complete control of the economic and political structures of our society have never considered it. Yet on they blather... agreggate consumer confidence... monetary easing... abracadbra... alakazam!

Whenever I get confronted with something like this the first time it clicks it is an almost Zen moment of knowing. Later I want to poke the guy who asked it in the eye with a stick.

Socrates got what he had coming.

Functionally Atheist

However, I live in what is, or at least some how appears to be, a real, material universe. By reality I mean what Phillip K. Dick put perfectly: "That which does not go away because you stop believing it." In that place, the only place we exist as far as others are concerned, the only medium through which we can communicate, there is no evidence of God. Nothing objective anyway.

The net effect is, when it comes to material reality I'm a stone cold materialist. I believe some ever more precise combination of physics (and all it entails) and reason will account for all that we experience. This is not to say there is no God, just that everything we've learned as we've turned away from ignorance and superstition has taught us God is not required.

I think that's about as close to falsifiability as you get with respect to God and God does not do well in the encounter.

On the other hand. Inside where I live, where my existence is a continuing play of symbols and metaphor, grasping for patterns in the waves of sensation constantly pouring over me, there is a place where I experience something larger than me. I don't know how else to describe it. I truly experience it rarely, but when I do. mostly in some sort of meditative state, or when genuinely at peace--sitting on a hillside on a warm spring day--I can see forever and feel the all of everything humming. A soft warmth in the darkness. Encompassing.

But totally subjective. I wouldn't think of trying to prove such a thing.

Ain Soph

Ain

.

is

Not!

God=Not

!God

Things I Found August 7, 2009

LAS VEGAS — It’s one of the most hostile hacker environments in the country –- the DefCon hacker conference held every summer in Las Vegas.

But despite the fact that attendees know they should take precautions to protect their data, federal agents at the conference got a scare on Friday when they were told they might have been caught in the sights of an RFID reader.

The reader, connected to a web camera, sniffed data from RFID-enabled ID cards and other documents carried by attendees in pockets and backpacks as they passed a table where the equipment was stationed in full view.

Read it all here.

AP ENTERPRISE: Federal tax revenues plummeting

AP ENTERPRISE: Plummeting tax revenues starve government just as Obama embarks on big plans

STEPHEN OHLEMACHER

AP News

Aug 03, 2009 19:51 EST

The recession is starving the government of tax revenue, just as the president and Congress are piling a major expansion of health care and other programs on the nation's plate and struggling to find money to pay the tab. The numbers could hardly be more stark...

Agog over Bush's comments on Gog and Magog

It's awkward to say openly, but now-departed President Bush is a religious crackpot, an ex-drunk of small intellect who "got saved." He never should have been entrusted with power to start wars.

For six years, Americans really haven't known why he launched the unnecessary Iraq attack. Official pretexts turned out to be baseless. Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction, after all, and wasn't in league with terrorists, as the White House alleged. Collapse of his asserted reasons led to speculation about hidden motives: Was the invasion loosed to gain control of Iraq's oil -- or to protect Israel -- or to complete Bush's father's old vendetta against the late dictator Saddam Hussein? Nobody ever found an answer.

Now, added to the other suspicions, comes the goofy possibility that arcane, supernatural Bible prophecies were a factor. This casts an ominous pall over the needless war that has killed more than 4,000 young Americans and cost U.S. taxpayers perhaps $1 trillion.

Pro Libertate: The Plague of Punitive Populism

The Plague of Punitive Populism

By William N. Grigg

"Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there."

-- Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath

I suggest that liberty-minded Americans... can learn much about themselves and those around them through [what] we could call the "Tom Joad Test."

I'm not a fan of Steinbeck's incurably wrong-headed economic views or his idiosyncratic collectivist politics in general, although I must admit a sneaking respect for anybody who attracts the hostile interest of the FBI solely on the strength of his published writings.

His creation Tom Joad isn't among my favorite fictional characters. But there is substantial merit in Joad's pledge to sympathize with those who are victims of Power.

Early in The Grapes of Wrath, Joad--recently paroled after serving four years in prison for killing a man who stabbed him in a fight -- becomes re-acquainted with Jim Casy, a fallen Oklahoma Pentecostal preacher who has embraced a populist version of Emerson's "oversoul" concept: "Maybe all men got one big soul ever'body's a part of."

Thus was planted the seed that would sprout into Joad's famous soliloquy, which included the pledge that "Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there."

So here, stated briefly, is the question that serves as the shibboleth/sibbolet dividing line in the "Tom Joad Test":

When you see a cop -- or, more likely, several of them -- beating up on a prone individual, do you instinctively sympathize with the assailant(s) or the victim?

If it's the former, you're an authoritarian, irrespective of your partisan attachments or professed political philosophy.

If it's the latter, you're an instinctive libertarian, whether or not you are consistently guided by that impulse in your political decisions.

It may later be demonstrated that the figure on the receiving end of the beating had committed some horrible crime. However, such a disclosure wouldn't invalidate the results of the Tom Joad Test, because that test reveals a subject's default assumptions about the relationship between the individual and the state.

Read it all here.

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

Things I Found August 5, 2009

It is unfortunately none too well understood that, just as the State has no money of its own, so it has no power of its own. All the power it has is what society gives it, plus what it confiscates from time to time on one pretext or another; there is no other source from which State power can be drawn. Therefore every assumption of State power, whether by gift or seizure, leaves society with so much less power. There is never, nor can there be, any strengthening of State power without a corresponding and roughly equivalent depletion of social power.

The broader question of where we go as a nation pulses with tragedy. History is clearly presenting us with a new set of mandates: get local, get finer, downscale, and get going on it right away. Prepare for it now or nature will whack you upside the head with it not too long from now. Attempting to maintain anything on the gigantic scale will turn out to be a losing proposition, whether it is military control of people in Central Asia, or colossal bureaucracies run in the USA, or huge factory farms, or national chain store retail, or hypertrophied state universities, or global energy supply networks.

These imperatives are so outside-the-box of ordinary experience right now, that to drag them into the arena of politics can only evoke blank stares or nervous giggling. But whether we like it or not, these are the things that will really matter in the years ahead — not whether General Motors can ever make a profit again, or what Target Store’s sales figures are next quarter, or whether the latest high-rise condo-and-gambling complex in Las Vegas will be successfully marketed.

Here, in the dog days of summer, it seems to me that the situation in the USA is so fundamentally bad, so unpromising, so booby-trapped for failure, that I wonder if there has ever been a society so badly deluded as ours. We’re prisoners of our wishes, living in a strange dream-time, oblivious to the forces gathering at the margins of our vision, lost in a wilderness of our own making.

James Howard Kunstler, Monumentally Tragic Disappointment on the Horizon

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

Things I Found August 4, 2009

The most dangerous man, to any government, is the man who is able to think things out for himself without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos. Almost inevitable he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane and intolerable, and so, if he is romantic, he tries to change it. And even if he is not romantic personally he is apt to spread discontent among those who are.

One of the most perversely misleading myths about government is that it promotes order within its own bailiwick, keeps groups from constantly warring with each other and somehow creates togetherness and harmony. In fact, that’s the exact opposite of the truth. There’s no cosmic imperative for different people to rise up against one another – unless they’re organized into political groups. The Middle East, now the world’s most fertile breeding ground for hatred, provides an excellent example.

Muslims, Christians and Jews lived together peaceably in Palestine, Lebanon and North Africa for centuries, until the situation became politicized after WWI. Until then an individual’s background and beliefs were just personal attributes, not a casus belli. Government was at its most benign, an ineffectual nuisance that concerned itself mostly with extorting taxes. People were busy with that most harmless of activities, making money.

But politics does not deal with people as individuals. It scoops them up into parties and nations. And some group inevitably winds up using the power of the state (however innocently or "justly" at first) to impose its values and wishes on others, with predictably destructive results. What would otherwise be an interesting kaleidoscope of humanity then sorts itself out according to the lowest common denominator peculiar to the time and place.

The Essence of Government, Doug Casey

Monday, August 3, 2009

Mandatory Binding Arbitration

I suppose the first sticking point I have is with the term mandatory. I'm already halfway out the door when I hear that.

As the editorialist said...

Most consumers aren't aware that many of the contracts they sign include these provisions. Even those aware of the provisions are helpless to do anything about them because consumers generally must accept contracts in their entirety. And some provisions -- such as those that force consumers to travel cross-country to attend arbitration hearings -- can be unfair.I suppose the caveat of freely entered into could apply. If you signed a contract a contract knowing the provisions contained in it, well, what can I say?

Courts from time to time have struck down extreme provisions, but there are no uniform national standards. Several bills pending in Congress attempt to address these inequities.

As Stefan Molyneux would say, "More guns will solve everything!"

The typical unreasoned response to the suggestion that if you remove coercive monopoly violence from the social equation is to protest that without the restraining hand of the state there would be no rules or order, people would just run around doing whatever they wanted. It would be a chaotic nightmare.

But what is more chaotic, abiding by the terms of a signed contract or facing the agreed upon sanctions or not knowing if the terms will be upheld because a judge or legislator can set them aside later in favor of one party or the other?

The state creates the very uncertainty and doubt it claims to be protecting us from.

Services that require you to accept onerous terms are not monsters of exploitation--well, maybe they are, but that's a different discussion. In this context they represent an opportunity for enterprising entrepreneurs. Offer the same service on better terms if you can. If you can't then don't turn to the someone with a gun to solve your problem for you.

The Washington Post

A Good Arbiter

Congress considers new laws regulating the resolution of disputes between businesses and consumers.Saturday, April 12, 2008; Page A14

VIRTUALLY everyone who carries a credit card is subject to something called a binding mandatory arbitration agreement. So is almost anyone who owns a cellphone or who recently purchased a car from a dealer.

These agreements are often buried deep in the fine print of consumer contracts; they mandate that any dispute between the consumer and the company be resolved through private arbitration. That means a neutral third party -- often a former judge -- rules on the issue, and both sides are bound by the decision. Arbitration is generally cheaper and speedier than litigation. Surveys show that business strongly favors it, while consumers are also generally approving.

Still, binding mandatory arbitration provisions in consumer contracts have come under attack recently, and for some good reasons. Most consumers aren't aware that many of the contracts they sign include these provisions. Even those aware of the provisions are helpless to do anything about them because consumers generally must accept contracts in their entirety. And some provisions -- such as those that force consumers to travel cross-country to attend arbitration hearings -- can be unfair. Courts from time to time have struck down extreme provisions, but there are no uniform national standards. Several bills pending in Congress attempt to address these inequities.

Sen. Russell Feingold (D-Wis.) would prohibit binding mandatory arbitration provisions in all consumer and employment contracts; the bill allows arbitration only after a dispute arises and only if both parties agree. This goes too far and risks eliminating arbitration as a serious alternative to litigation for such routine matters as warranty disputes, as even some supporters of the bill acknowledge. Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.) provides a better framework to improve the system. Mr. Sessions's bill would, among other things, force companies to more prominently display arbitration provisions and provide an explanation of how the costs of the arbitration are to be split between consumer and business. The bill also would allow consumers to opt out of arbitration in favor of small-claims court. Any hearing would have to take place in a location convenient to the consumer, and arbitrators would be required to apply the laws of the state in which the consumer resides.

This week, Sens. Mel Martinez (R-Fla.) and Herb Kohl (D-Wis.) introduced legislation to ban mandatory arbitration clauses in nursing home contracts. This narrow exception may be warranted. Nursing home residents are among the most vulnerable in the country, and decisions to place family members in these facilities are often made under the most stressful of circumstances. Allowing residents or their families to sue may be the only way to prod nursing homes to improve care.

The Injustice of Private Arbitration

Monday, April 21, 2008; Page A14

Your April 12 editorial "A Good Arbiter" completely ignored the high upfront costs, the heavy anti-consumer bias and the gross procedural disadvantages that characterize private arbitration as opposed to our public courts of law.

These features are why consumer groups, patient advocates, employment rights activists -- essentially everyone besides the corporate lobby -- generally oppose mandatory arbitration of disputes between corporations and regular people.

Arbitration creates grave injustices for the up to 20 percent of American workers who, to keep or get jobs, must waive their constitutional right to take lawbreaking employers to court. If their employer underpays, discriminates against, denies workers' compensation to or otherwise illegally mistreats employees, the employer's handpicked private arbitration company will hear the dispute.

Unlike the measure from Sen. Russell Feingold (D-Wis.), the bill by Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.) does absolutely nothing for the most financially vulnerable Americans, who in this economy must choose between much-needed employment opportunities and much-cherished constitutional rights. More is at stake here than $200 cellphone contract disputes that can be taken to small-claims court.

KIA C. FRANKLIN

Senior Fellow in Civil Justice

Drum Major Institute for Public Policy

New York

Everyday Anarchy Moving.

I'm am reserving this space for more informal purposes and day-to-day stuff.

I think getting Everyday Anarchy and Practical Anarchy in HTML format is important. Molyneux makes strong arguments. It's good to have a ready reference for them. Being able to link to them directly as opposed to a PDF will be more likely to drive others to read them, perhaps the ideas will sink in.

One can always hope.

Sunday, August 2, 2009

Spontaneous Order

The study of complexity, or chaos, informs us of patterns of regularity that lie hidden in our world, but which spontaneously manifest themselves to generate the order that we like to pretend authorities have created for us. There is much to discover about the interplay of unseen forces that work, without conscious direction, to make our lives more productive and peaceful than even the best-intended autocrat can accomplish. As the disruptive histories of state planning and regulation reveal, efforts to impose order by fiat often produce disorder, a phenomenon whose explanation is to be found in the dynamical nature of complexity. In the words of Terry Pratchett: "Chaos is found in greatest abundance wherever order is being sought. Chaos always defeats order because it is better organized." ~ Butler Shaffer

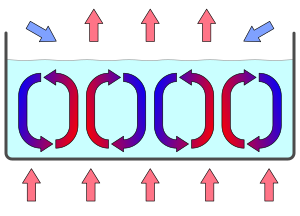

If we progressively increase the temperature of the bottom plane, there will be a temperature at which something dramatic happens in the liquid: convection cells will appear. The microscopic random movement spontaneously becomes ordered on a macroscopic level, with a characteristic correlation length. The rotation of the cells is stable and will alternate from clock-wise to counter-clockwise as we move along horizontally: there is a spontaneous symmetry breaking.

[T]he deterministic law at the microscopic level produces a non-deterministic arrangement of the cells: if you reproduce the experiment many times, a particular position in the experiment will be in a clockwise cell in some cases, and a counter-clockwise cell in others. Microscopic perturbations of the initial conditions are enough to produce a macroscopic effect: this is an example of the Butterfly effect from Chaos theory.

Anarchy: You're Doing It Right! (Already)

Stephan Kinsella

If most people did not already have the character to voluntarily respect most of their neighbors’ rights, society and civilization would be impossible. Most people are good enough to permit civilization to occur, despite the existence of some degree of public and private crime.

Butler Shaffer

I am often asked if anarchy has ever existed in our world, to which I answer: almost all of your daily behavior is an anarchistic expression. How you deal with your neighbors, coworkers, fellow customers in shopping malls or grocery stores, is often determined by subtle processes of negotiation and cooperation. Social pressures, unrelated to statutory enactments, influence our behavior on crowded freeways or grocery checkout lines. If we dealt with our colleagues at work in the same coercive and threatening manner by which the state insists on dealing with us, our employment would be immediately terminated. We would soon be without friends were we to demand that they adhere to specific behavioral standards that we had mandated for their lives.

Should you come over to our home for a visit, you will not be taxed, searched, required to show a passport or driver’s license, fined, jailed, threatened, handcuffed, or prohibited from leaving. I suspect that your relationships with your friends are conducted on the same basis of mutual respect. In short, virtually all of our dealings with friends and strangers alike are grounded in practices that are peaceful, voluntary, and devoid of coercion.

Stefan Moylneux

For instance, take dating, marriage and family.

In any reasonably free society, these activities do not fall in the realm of political coercion. No government agency chooses who you are to marry and have children with, and punishes you with jail for disobeying their rulings. Voluntarism, incentive, mutual advantage - dare we say "advertising"? - all run the free market of love, sex and marriage.

What about your career? Did a government official call you up at the end of high school and inform you that you were to become a doctor, a lawyer, a factory worker, a waiter, an actor, a programmer - or a philosopher? Of course not. You were left free to choose the career that best matched your interests, abilities and initiative.

What about your major financial decisions? Each month, does a government agent come to your house and tell you exactly how much you should save, how much you should spend, whether you can afford that new couch or old painting? Did you have to apply to the government to buy a new car, a new house, a plasma television or a toothbrush?

No, in all the areas mentioned above - love, marriage, family, career, finances - we all make our major decisions in the complete absence of direct political coercion.

Thus - if anarchy is such an all-consuming, universal evil, why is it the default - and virtuous - freedom that we demand in order to achieve just liberty in our daily lives?

If the government told you tomorrow that it was going to choose for you where to live, how to earn your keep, and who to marry - would you fall to your knees and thank the heavens that you have been saved from such terrible anarchy - the anarchy of making your own decisions in the absence of direct political coercion?

Of course not - quite the opposite - you would be horrified, and would oppose such an encroaching dictatorship with all your might.

This is what I mean when I say that we consider anarchy to be an irreducible evil - and also an irreducible good. It is both feared and despised - and considered necessary and virtuous.

If you were told that tomorrow you would wake up and there would be no government, you would doubtless fear the specter of "anarchy."

If you were told tomorrow that you would have to apply for a government permit to have children, you would doubtless fear the specter of "dictatorship," and long for the days of "anarchy," when you could decide such things without the intervention of political coercion.

Thus we can see that we human beings are deeply, almost ferociously ambivalent about "anarchy." We desperately desire it in our personal lives, and just as desperately fear it politically.

Today In Oleomargarine History

The Oleomargarine Act established the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) laboratory system, 1886.

From *The Old Farmer's Almanac*.

How much you wanna bet it was stuck in as a rider on some unread amendment? For the children!

Arguing From First Principles

[A]nyone who is not an anarchist must maintain either: (a) aggression is justified; or (b) states (in particular, minimal states) do not necessarily employ aggression.

Proposition (b) is plainly false. States always tax their citizens, which is a form of aggression. They always outlaw competing defense agencies, which also amounts to aggression. (Not to mention the countless victimless crime laws that they inevitably, and without a single exception in history, enforce on the populace. Why minarchists think minarchy is even possible boggles the mind.)

As for (a), well, socialists and criminals also feel aggression is justified. This does not make it so. Criminals, socialists, and anti-anarchists have yet to show how aggression – the initiation of force against innocent victims – is justified. No surprise; it is not possible to show this. But criminals don’t feel compelled to justify aggression; why should advocates of the state feel compelled to do so?

Conservative and minarchist-libertarian criticism of anarchy on the grounds that it won’t "work" or is not "practical" is just confused. Anarchists don’t (necessarily) predict anarchy will be achieved – I for one don’t think it will. But that does not mean states are justified.

[U]tilitarian replies like "but we need a state" do not contradict the claim that states employ aggression and that aggression is unjustified. It simply means that the state-advocate does not mind the initiation of force against innocent victims – i.e., he shares the criminal/socialist mentality. The private criminal thinks his own need is all that matters; he is willing to commit violence to satisfy his needs; to hell with what is right and wrong. The advocate of the state thinks that his opinion that "we" "need" things justifies committing or condoning violence against innocent individuals. It is as plain as that. Whatever this argument is, it is not libertarian. It is not opposed to aggression. It is in favor of something else – making sure certain public "needs" are met, despite the cost – but not peace and cooperation. The criminal, gangster, socialist, welfare-statist, and even minarchist all share this: they are willing to condone naked aggression, for some reason. The details vary, but the result is the same – innocent lives are trampled by physical assault. Some have the stomach for this; others are more civilized – libertarian, one might say – and prefer peace over violent struggle.

Audit The Fed

When we want to know what's in theirs we get one of these.

You have a congressional representative...

H.R. 1207: Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2009

...and two senators.

S. 604: Federal Reserve Sunshine Act of 2009

Make them do their job.

U.S. Constitution - Article 1 Section 8

The Congress shall have Power To... coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin...

Everyday Anarchy 04: Anarchy And History

EVERYDAY ANARCHY

By Stefan Molyneux

ANARCHY AND HISTORY

Our clichéd vision of the typical anarchist tends to see him emerging shortly before World War I, which is very interesting when you think about it. The stereotypical anarchist is portrayed as a feverish failure, who uses his political ideology as a self-righteous cover for his lust for violence. He claims he wishes to free the world from tyranny, when in fact all he wants to do is to break bones and take lives.

We typically view this anarchist as a form of terrorist, which is generally defined as someone committed to the use of violence to achieve political ends, and place both in the same category as those who attempt a military coup against an existing government.

However, when you break it down logically, it seems almost impossible to provide a definition of terrorism which does not also include political leaders, or at least the political process itself.

The act of war is itself an attempt to achieve political ends through the use of violence - the annexation of property, the capturing of a new tax base, or the overthrow of a foreign government - and it always requires a government that is willing and able to increase the use of violence against its own citizens, through tax increases and/or the military draft. Even defending a country against invasion inevitably requires an escalation of the use of force against domestic citizens.

Thus how can we easily divide those outside the political process who use violence to achieve their goals from those within the political process who use violence to achieve their goals? It remains a daunting task, to say the least.

What is fascinating about the mythology of the "evil anarchists" - and mythology it is - is that even if we accept the stereotype, the disparity in body counts between the anarchists and their enemies remains staggeringly misrepresented, to say the least.

Anarchists in the period before the First World War killed perhaps a dozen or a score of people, almost all of them state heads or their representatives.

On the other hand, state heads or their representatives caused the deaths of over 10 million people through the First World War.

If we value human life - as any reasonable and moral person must - then fearing anarchists rather than political leaders is like fearing spontaneous combustion rather than heart disease. In the category of "causing deaths," a single government leader outranks all anarchists tens of thousands of times.

Does this seem like a surprising perspective to you? Ah, well that is what happens when you look at the facts of the world rather than the stories of the victors. Another example would be an objective examination of murder and violence in 19th- century America. The typical story about the "Wild West" is that it was a land populated by thieves, brigands and murderers, where only the "thin blue line" of the lone local sheriffs stood between the helpless townspeople and the endless predations of swarthy and unshaven villains.

If we look at the simple facts, though, and contrast the declining 19th century US murder rates with the 600,000 murders committed in the span of a few years by the government- run Civil War, we can see that the sheriffs were not particularly dedicated to protecting the helpless townspeople, but rather delivering their money, their lives and their children to the state through the brutal enforcement of taxation and military enslavement.

When we look at an institution such as slavery, we can see that it survived, fundamentally, on two central pillars - patronizing and fear-mongering mythologies, and the shifting of the costs of enforcement to others.

What justifications were put forward, for instance, for the enslavement of blacks? Well, the "white man's burden," or the need to "Christianize" and civilize these savage heathens - this was the condescension - and also because if the slaves were turned free, plantations would be burned to the ground, pale-throated women would be savagely violated, and all the endless torments of violence and destruction would be wreaked upon society - this was the fear-mongering mythology!

Slavery as an institution could not conceivably survive economically if the slave owners had to pay for the actual expense of slavery themselves. Shifting the costs of the capture, imprisonment and return of slaves to the general taxpayer was the only way that slavery could remain profitable. The use of the political coercion required to make slavery profitable, of course, generates a great demand for mythological "cover-ups," or ideological distractions from the violence at the core of the institution. Thus violence always requires intellectualization, which is why governments always want to fund higher education and subsidize intellectuals. We shall get to more of this later.

Even outside war, in the 20th century alone, more than 270 million people were murdered by their governments. Compared to the few dozen murders committed by anarchists, it is hard to see how the fantasy of the "evil anarchist" could possibly be sustained when we compare the tiny pile of anarchist bodies to the virtual Everest of the dead heaped by governments in one century alone.

Surely if we are concerned about violence, murder, theft and rape, we should focus on those who commit the most evils - political leaders - rather than those who oppose them, even misguidedly. If we accept that political leaders murder mankind by the hundreds of millions, then we may even be tempted to have a shred of sympathy for these "evil anarchists," just as we would for a man who shoots down a rampaging mass murderer.

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Everyday Anarchy 03: Ambivalence and Bigotry

EVERYDAY ANARCHY

By Stefan Molyneux

AMBIVALENCE AND BIGOTRY

It is a truism - and I for one think a valid one - that the simple mind sees everything in black or white. Wisdom, on the other hand, involves being willing to suffer the doubts and complexities of ambivalence.

The dark-minded bigot says that all blacks are perfidious; the light-minded bigot says that all blacks are victims. The misogynist says that all women are corrupt; the feminist often says that all women are saints.

Exploring the complexities and contradictions of life with an open-minded fairness - neither with the imposition of premature judgment, nor the withholding of judgment once the evidence is in - is the mark of the scientist, the philosopher - of a rational mind.

The fundamentalists among us ascribe all mysteries to the "will of God" - which answers nothing at all, since when examined, the "will of God" turns out to be just another mystery; it is like saying that the location of my lost keys is "the place where my keys are not lost" - it adds nothing to the equation other than a teeth-gritting tautology. Mystery equals mystery. Anyone with more than half a brain can do little more than roll his eyes.

The immaturity of jumping to premature and useless conclusions is matched on the other hand only by the shallow and frightened fogs of modern - or perhaps I should say post- modern - relativism, where no conclusions are ever valid, no absolute statements are ever just - except that one of course - and everything is exploration, typically blindfolded, and without a compass. There is no destination, no guidepost, no sense of progress, no building to a greater goal - it is the endless dissection of cultural cadavers without even a definition of health or purpose, which thus comes perilously close to looking like fetishistic sadism.

The simple truth is that some black men are good, and some black men are bad, and most black men are a mixture, just as we all are. Some women are treacherous; some women are saints. "Blackness" or "gender" is an utterly useless metric when it comes to evaluating a person morally; it is about as helpful as trying to use an iPod to determine which way is north. The phrase "sexual penetration" does not tell us whether the act is consensual or not--saying that sexual penetration is always evil is as useless as saying that it is always good.

In the same way, some anarchism is good (notably that which we treasure so much in our personal lives) and some anarchism is bad (notably our fears of violent chaos, bomb- throwing and large mustaches). As a word, however, "anarchism" does nothing to help us evaluate these situations. Applying foolish black-and-white thinking to complex and ambiguous situations is just another species of bigotry

Claiming that "anarchism" is both rank political evil and the greatest treasure in our personal lives is a contradiction well worth examining, if we wish to gain some measure of mature wisdom about the essential questions of truth, virtue and the moral challenges of social organization.

Everyday Anarchy 2: Everyday Anarchy

EVERYDAY ANARCHY

By Stefan Molyneux

EVERYDAY ANARCHY

For instance, take dating, marriage and family.

In any reasonably free society, these activities do not fall in the realm of political coercion. No government agency chooses who you are to marry and have children with, and punishes you with jail for disobeying their rulings. Voluntarism, incentive, mutual advantage - dare we say "advertising"? - all run the free market of love, sex and marriage.

What about your career? Did a government official call you up at the end of high school and inform you that you were to become a doctor, a lawyer, a factory worker, a waiter, an actor, a programmer - or a philosopher? Of course not. You were left free to choose the career that best matched your interests, abilities and initiative.

What about your major financial decisions? Each month, does a government agent come to your house and tell you exactly how much you should save, how much you should spend, whether you can afford that new couch or old painting? Did you have to apply to the government to buy a new car, a new house, a plasma television or a toothbrush?

No, in all the areas mentioned above - love, marriage, family, career, finances - we all make our major decisions in the complete absence of direct political coercion.

Thus - if anarchy is such an all-consuming, universal evil, why is it the default - and virtuous - freedom that we demand in order to achieve just liberty in our daily lives?

If the government told you tomorrow that it was going to choose for you where to live, how to earn your keep, and who to marry - would you fall to your knees and thank the heavens that you have been saved from such terrible anarchy - the anarchy of making your own decisions in the absence of direct political coercion?

Of course not - quite the opposite - you would be horrified, and would oppose such an encroaching dictatorship with all your might.

This is what I mean when I say that we consider anarchy to be an irreducible evil - and also an irreducible good. It is both feared and despised - and considered necessary and virtuous.

If you were told that tomorrow you would wake up and there would be no government, you would doubtless fear the specter of "anarchy."

If you were told tomorrow that you would have to apply for a government permit to have children, you would doubtless fear the specter of "dictatorship," and long for the days of "anarchy," when you could decide such things without the intervention of political coercion.

Thus we can see that we human beings are deeply, almost ferociously ambivalent about "anarchy." We desperately desire it in our personal lives, and just as desperately fear it politically.

Another way of putting this is that we love the anarchy we live, and yet fear the anarchy we imagine.

One more point, and then you can decide whether my patient is beyond hope or not.

It has been pointed out that a totalitarian dictatorship is characterized by the almost complete absence of rules. When Solzhenitsyn was arrested, he had no idea what he was really being charged with, and when he was given his 10-year sentence, there was no court of appeal, or any legal proceedings whatsoever. He had displeased someone in power, and so it was off to the gulags with him!

When we examine countries where government power is at its greatest, we see situations of extreme instability, and a marked absence of objective rules or standards. The tinpot dictatorships of third world countries are regions arbitrarily and violently ruled by gangs of sociopathic thugs.

Closer to home, for most of us, is the example of inner-city government-run schools, ringed by metal detectors, and saturated with brutality, violence, sexual harassment, and bullying. The surrounding neighborhoods are also under the tight control of the state, which runs welfare programs, public housing, the roads, the police, the buses, the hospitals, the sewers, the water, the electricity and just about everything else in sight. These sorts of neighborhoods have moved beyond democratic socialism, and actually lie closer to dictatorial communism.

Similarly, when we think of these inner cities as a whole, we can also understand that the majority of the endemic violence results from the drug trade, which directly resulted from government bans on the manufacture and sale of certain kinds of drugs. Treating drug addiction rather than arresting addicts would, it is estimated, reduce criminal activity by up to 80%.

Here, again, where there is a concentration of political power, we see violence, mayhem, shootings, stabbings, rapes and all the attendant despair and nihilism - everything that "anarchism" is endlessly accused of!

What about prisons, where political power is surely at its greatest? Prisons seethe with rapes, murders, stabbings and assaults - not to mention drug addiction. Sadistic guards beat on sadistic prisoners, to the point where the only difference at times seems to be the costumes. Here we have a "society" that seems like a parody of "anarchy" - a nihilistic and ugly universe usually described by the word "anarchy" which actually results from a maximization of political power, or the exact opposite of "anarchy."

Now, we certainly could argue that yes, it may be true that an excess of political power breeds anarchy - but that a deficiency of political power breeds anarchy as well! Perhaps "order" is a sort of Aristotelian mean, which lies somewhere between the chaos of a complete absence of political coercion, and the chaos of an excess of political coercion.

However, we utterly reject that approach in the other areas mentioned above - love, marriage, finances, career etc. We understand that any intrusion of political coercion into these realms would be a complete disaster for our freedoms. We do not say, with regards to marriage, "Well, we wouldn't want the government choosing everyone's spouse - but neither do we want the government having no involvement in choosing people spouses! The correct amount of government coercion lies somewhere in the middle."

No, we specifically and unequivocally reject the intrusion of political coercion into such personal aspects of our lives.

Thus once more we must at least recognize the basic paradox that we desperately need and desire the reality of anarchy in our personal lives - and yet desperately hate and fear the idea of anarchy in our political environment.

We love the anarchy we live. We fear the anarchy we imagine - the anarchy we are taught to fear.

Until we can discuss the realities of our ambivalence towards this kind of voluntarism, we shall remain fundamentally stuck as a species - like any individual who wallpapers over his ambivalence, we shall spend our lives in distracted and oscillating avoidance, to the detriment of our own present, and our children's future.

This is why I cannot just let this patient die. I still feel a heartbeat - and a strong one too!

Everyday Anarchy 1: Introduction

EVERYDAY ANARCHY

By Stefan Molyneux

INTRODUCTION

It's hard to know whether a word can ever be rehabilitated - or whether the attempt should even be made.

Words are weapons, and can be used like any tools, for good or ill. We are all aware of the clichéd uses of such terms as "terrorists" versus "freedom fighters" etc. An atheist can be called an "unbeliever"; a theist can be called "superstitious." A man of conviction can be called an "extremist"; a man of moderation "cowardly." A free spirit can be called a libertine or a hedonist; a cautious introvert can be labeled a stodgy prude.

Words are also weapons of judgment - primarily moral judgment. We can say that a man can be "freed" of sin if he accepts Jesus; we can also say that he can be "freed" of irrationality if he does not. A patriot will say that a soldier "serves" his country; others may take him to task for his blind obedience. Acts considered "murderous" in peacetime are hailed as "noble" in war, and so on.

Some words can never be rehabilitated - and neither should they be. Nazi, evil, incest, abuse, rape, murder - these are all words which describe the blackest impulses of the human soul, and can never be turned to a good end. Edmund may say in King Lear, "Evil, be thou my good!" but we know that he is not speaking paradoxically; he is merely saying "that which others call evil - my self-interest - is good for me."

The word "anarchy" may be almost beyond redemption - any attempt to find goodness in it could well be utterly futile - or worse; the philosophical equivalent of the clichéd scene in hospital dramas where the surgeon blindly refuses to give up on a clearly dead patient.

Perhaps I'm engaged in just such a fool's quest in this little book. Perhaps the word "anarchy" has been so abused throughout its long history, so thrown into the pit of incontestable human iniquity that it can never be untangled from the evils that supposedly surround it.

What images spring to mind when you hear the word "anarchy"? Surely it evokes mad riots of violence and lawlessness - a post-apocalyptic Darwinian free-for-all where the strong and evil dominate the meek and reasonable. Or perhaps you view it as a mad political agenda, a thin ideological cover for murderous desires and cravings for assassinations, where wild-eyed, mustachioed men with thick hair and thicker accents roll cartoon bombs under the ornate carriages of slowly-waving monarchs. Or perhaps you view "anarchy" as more of a philosophical specter; the haunted and angry mutterings of over-caffeinated and seemingly-eternal grad students; a nihilistic surrender to all that is seductive and evil in human nature, a hurling off the cliff of self-restraint, and a savage plunge into the mad magic of the moment, without rules, without plans, without a future...

If your teenage son were to come home to you one sunny afternoon and tell you that he had become an anarchist, you would likely feel a strong urge to check his bag for black hair dye, fresh nose rings, clumpy mascara and dirty needles. His announcement would very likely cause a certain trapdoor to open under your heart, where you may fear that it might fall forever. The heavy syllables of words like "intervention," "medication," "boot camp," and "intensive therapy" would probably accompany the thudding of your quickened pulse.

All this may well be true, of course - I may be thumping the chest of a broken patient long since destined for the morgue, but certain... insights, you could say, or perhaps correlations, continue to trouble me immensely, and I cannot shake the fear that it is not anarchy that lies on the table, clinging to life - but rather, the truth.

I will take a paragraph or two to try and communicate what troubles me so much about the possible injustice of throwing the word "anarchy" into the pit of evil - if I have not convinced you by the end of the next page that something very unjust may be afoot, then I will have to continue my task of resurrection with others, because I do not for a moment imagine that I would ever convince you to call something good that is in fact evil.

And neither would I want to.

Now the actual meaning of the word "anarchy" is (from the OED):

- Absence of government; a state of lawlessness due to the absence or inefficiency of the supreme power; political disorder.

- A theoretical social state in which there is no governing person or body of persons, but each individual has absolute liberty (without implication of disorder).

Thus we can see that the word "anarchy" represents two central meanings: an absence of both government and social order, and an absence of government with no implication of social disorder.

Without a government...

What does that mean in practice?

Well, clearly there are two kinds of leaders in this world - those who lead by incentive, and those who lead by force. Those who lead by incentive will offer you a salary to come and work for them; those who lead by force will throw you in jail if you do not pick up a gun and fight for them.

Those who lead by incentive will try to get you to voluntarily send your children to their schools by keeping their prices reasonable, their classes stimulating, and demonstrating proven and objective success.

Those who lead by force will simply tell you that if you do not pay the property taxes to fund their schools, you will be thrown in jail.

Clearly, this is the difference between voluntarism and violence.

The word "anarchy" does not mean "no rules." It does not mean "kill others for fun." It does not mean "no organization."

It simply means: "without a political leader."

The difference, of course, between politics and every other area of life is that in politics, if you do not obey the government, you are thrown in jail. If you try to defend yourself against the people who come to throw you in jail, they will shoot you.

So - what does the word "anarchy" really mean?

It simply means a way of interacting with others without threatening them with violence if they do not obey.

It simply means "without political violence."

The difference between this word and words like "murder" and "rape" is that we do not mix murder and rape with the exact opposite actions in our life, and consider the results normal, moral and healthy. We do not strangle a man in the morning, then help a woman across the street in the afternoon, and call ourselves "good."

The true evils that we all accept - rape, assault, murder, theft - are never considered a core and necessary part of the life of a good person. An accused murderer does not get to walk free by pointing out that he spent all but five seconds of his life not killing someone.

With those acknowledged evils, one single transgression changes the moral character of an entire life. You would never be able to think of a friend who is convicted of rape in the same way again.

However - this is not the case with "anarchy" - it does not fit into that category of "evil" at all.

When we think of a society without political violence - without governments - these specters of chaos and brutality always arise for us, immediately and, it would seem, irrevocably.

However, it only takes a moment of thought to realize that we live the vast majority of our actual lives in complete and total anarchy - and call such anarchy "morally good."

Everyday Anarchy 0: Preluding thoughts

Please feel free to distribute this book to whomever you think would benefit from it, but please do not modify the contents.What follows, probably sporadically, will be excerpts from Molyneux' ebooks. I am posting them in sections, unmodified save for formatting within the context of this blog. Should you come across this and feel compelled to comment, by all means, indulge yourself.

I Guess This Means OK

I will admit my laziness on not looking very hard for copyrights or lefts on your ebooks. Everyday Anarchy and Practical Anarchy, for instance, both of which I immensely enjoyed, are chock full of good stuff. PDFs, however are not the most accessible or linkable as cites. I am sorely tempted to convert them both to html on one, the other or another of my blogs.

By why of self incrimination I offer this. I find myself engaged in the arena of ideas, often tipping my hat to you for distilling things down to principles. In those situations having some of your already honed stuff to toss out there is helpful. If you don't mind I will eventually have them all done, section by section. If you do mind just say the word and I will cease.

Peace,

Puck

To which he replied...

Thanks, I really appreciate that, you also might be interested in a recent debate I had 2004 presidential candidate Michael Badnarik, where I discuss these ideas in more detail, based on audience questions:

*http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1ZaMgOh_J4 *

Stefan Molyneux, MA

Host, Freedomain Radio

www.freedomainradio.com

I guess it means he appreciates me posting entire section of his free books, such as Everyday Anarchy and Practical Anarchy and he's OK with it. OK, Stefan, until I hear otherwise that's my story and I'm sticking to it.

*Note: that link does not go to the debate, it just goes to a short blurb about the debate. As far as I know it is only available in audio which is free here.

Turtles All The Way Down

Turtles All The Way Down

By Stefan Molyneux

According to an apocryphal story, a well-known scientist was describing to an audience how the Earth orbits the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits the centre of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of his lecture, a little old lady got up and said: “This is all nonsense. Everybody knows that the world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant turtle.”

The scientist smiled and said, “I see. Can you tell, me, then, what is the turtle standing on?”

“You’re very clever, young man,” replied the old lady with a prim smile. “But it’s turtles all the way down!”

This story neatly captures the logical foolishness of the “Infinite Regression.” It is a tale pregnant with meaning for Libertarians, for we face some version of it almost every time we open our mouths.

The appeal to political authority in all its forms is really an attempt to bypass the black hole of Infinite Regression.

Here’s a pro-state argument we are all intimately familiar with:

Bad people like to use force to prey on good people.

Good people require a government to protect them from bad people.

This government, in order to be the final arbiter, must possess overwhelming force.

The logical madness is clear. Since bad people like using force to prey on good people, and the government is the greatest concentration of force in society, it stands to inevitable reason that bad people will use the government to prey on good people.

This is the central problem of Infinite Regression: who will watch the watchers? There is, of course, no rational or political answer.

The appeal to political authority in all its forms is really an attempt to bypass the black hole of Infinite Regression.

Here’s a pro-state argument we are all intimately familiar with:

Bad people like to use force to prey on good people.

Good people require a government to protect them from bad people.

This government, in order to be the final arbiter, must possess overwhelming force.

The logical madness is clear. Since bad people like using force to prey on good people, and the government is the greatest concentration of force in society, it stands to inevitable reason that bad people will use the government to prey on good people.

This is the central problem of Infinite Regression: who will watch the watchers? There is, of course, no rational or political answer.

Rejecting all “arguments” based on the Infinite Regression fallacy can unleash prodigious creativity. What has been sometimes called the single greatest idea in the history of the world arose from Darwin’s failure to be impressed by the Infinite Regression paradoxes of creationism. Free markets – and economics in general – arose from the failure of Ricardo and Smith to be impressed by the Infinite Regression argument that the nobility should manage resources on behalf of everyone else.

In the realm of morality, the problems of Infinite Regression are, literally, genocidal. The fantasy that a minority of men can justly force obedience from everyone else is responsible for more deaths than any other single delusion. In the realm of morality and the use of force, there is simply no solution to the problems of Infinite Regression. A stateless society is the only answer.

Any fundamentally rational philosophy must reject arguments that pass anywhere near the black hole of Infinite Regression. Appeals to the “virtuous violence” of the state instantly self-destruct, because of Infinite Regression. Demands for “obedience to gods” instantly self-destruct, since there must then be an infinite chain of more powerful gods, all obeying the “god above,” which would instantly result in a truly bureaucratic cosmic paralysis. Even merely mortal parents who attempt to justify their commandments through appeals to power, biology or position fall into the gravity well of Infinite Regression.

The three traditional power centers – politicians, priests and most parents – all justify their authority based on Infinite Regression fantasies. If mankind continues to believe in any moral authority except logical consistency and evidence, we will continue to sail blithely over the edge of the old lady’s imaginary plate, falling forever.

As the turtles descend, so do we.

Variables

Have you ever met anyone who argued that murder is the highest moral good, or that rape is a man's best course of action, or that the Golden Rule is: steal everything you can get your hands on, all the time?

Of course not.

Most people already consider violence and theft to be morally wrong. However, as morality gets more abstract, it gets harder and harder for people to maintain their consistency. I can’t even count the number of times people have agreed with me that “theft is wrong,” but who then instantly become baffled when I reply “therefore taxation is wrong.”

It’s the same with the military. No one has any trouble with the equation:

Man + murder = evilThrow in one little inconsequential variable, however, and most people get very confused

Man + murder + green costume = ?zzttz¿¡[short circuit] um, national hero?Universal Morality: A Proposition, by Stefan Molyneux.